“Art is art when what is made unmakes itself in the making and realizes, in barely recognizable form, the discordant truth of living life.”

Self-taught crochet artist Kelly Limerick is known for her large-scale installations and collaborations with global brands the likes of Disney and Gucci. While she is no stranger to the contemporary art scene through her projects with Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay and OH! Open House, Unbecoming is the first time that she is putting out a corpus of new personal work in a solo exhibition with an art gallery, Cuturi Gallery (Singapore).

Unbecoming takes her exploration of the crochet medium to another level, centering the focus on the process of the craft – ironically, through the reverse gesture of destruction. In the titular series, the artist torches five vases that she had meticulously crocheted.

This exhibition features works that emerge from this process, as well as an accompanying video installation that documents the unmaking process and a series of photographs that memorialise the vessels as they had once been. To execute her vision, Limerick brings on board Singaporean photographer Clarence Aw and Berlin-based film director Joy Song. Viewers are invited to bear witness to her works’ process of unbecoming, and in doing so, ponder the fraught relations between value, worth, labour and craft.

In a time when to live means to contend with the various global crises - ecological, humanitarian, economic - of our times, Unbecoming embodies the discordant truth of living life. At the same time, they are the fruits of the artist’s intensely personal creative tribulations, and mark a breakthrough in her creative practice. While Limerick’s previous works have often turned heads due to their intricate construction and visual appeal, it is here that she tears apart the crochet medium, and through this paradox of unmaking generates new conversations about an art form that she has been exploring for more than two decades.

Text by Michelle JN Lim

This exhibition was made possible with the support from Shaw Contract.

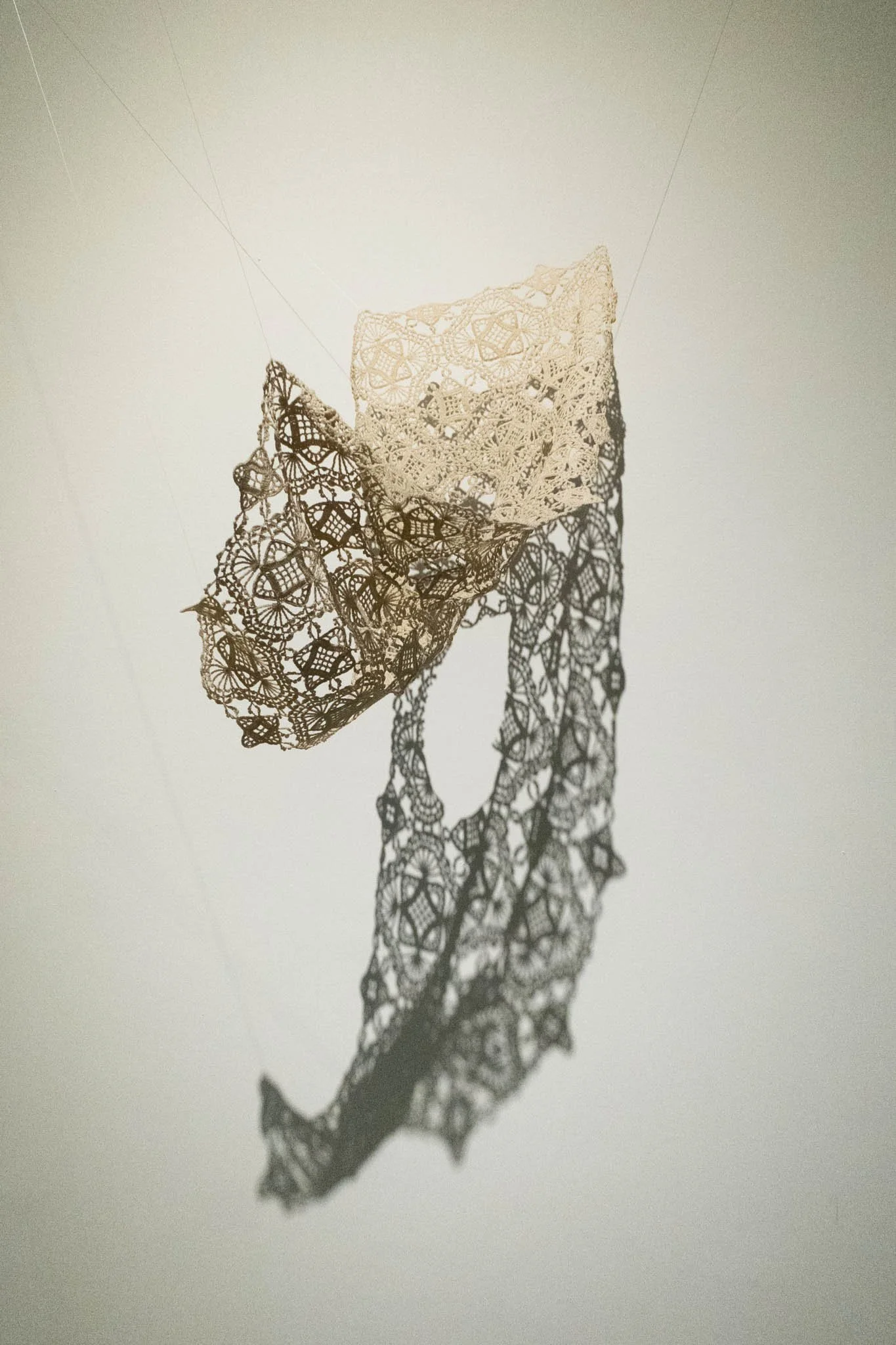

Unbecoming: Photographic prints

(Produced in collaboration with Clarence Aw)

Upon entering the gallery, visitors are greeted with 5 photographic prints of the crocheted vases on translucent fabric. Shot before the vases are irreversibly torched, these prints will not be reproduced again, representing a unique imprint of the vases’ ‘souls’ before they evolve into a different state.

Named after human characteristics that are usually deemed as negative, these prompt the viewer to question the negative or positive connotations tied to certain adjectives.

Installation view of photographic prints

Photo by Clarence Aw

Unbecoming: Film

(A film by Joy Song featuring the artworks of Kelly Limerick)

Walking through a curtain allowing us to transit into a different frame of mind, we are welcomed into an enclosed space to witness the very act of destruction. Viewing the vases from different perspectives, we become immersed in other worldly terrains as the nylon yarn bubbles and froths in response to the flame. The close-ups invite us to observe how the material reacts, while feeling that little heartache from seeing a product of labour unfurl.

Watching the vases disintegrate, we can only anticipate what awaits us in the next space peeking from behind a mysterious curtain made up of the very yarn used to create the works.

Director: Joy Song / Cinematographer: Bong / Grip: Ho Zhen Jie / Junior Grip: Melvin Han / Editor: Joy Song / Colourist: Eugene Seah

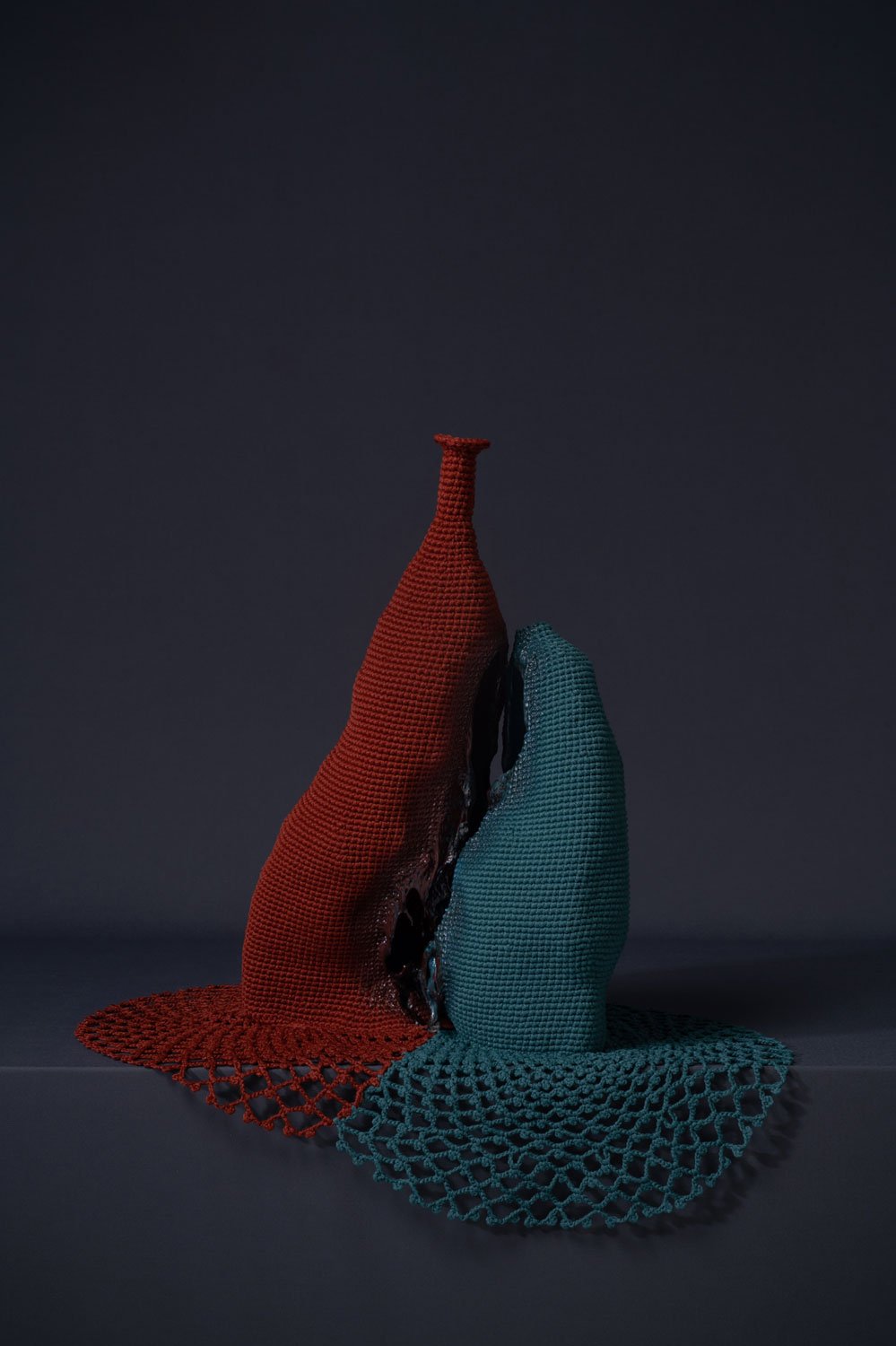

Unbecoming: Vase series

The artist’s recent exploration of vases in crochet prompts viewers to re-examine their idea of crochet as a ‘soft’ medium. Playing with the tension of the stitches, her crocheted vases are self-supported, silhouetted in structured lines. These vases are open-bottomed— revoking their identity as a ‘vessel’— and is each connected to a lace doily contrasted against its hard lines. In rendering these vases as completely ‘functionless’, the artist forces viewers to consider their perception of value in modern society.

Upon completion, the artist then torches the vases crocheted in nylon, causing them to melt and deform. Turning molten and then hardening into a plastic-like texture, the destroyed parts of the vessels become hard, but brittle. Again, the artist challenges the notions of perception— the soft crocheted vases display strength in their flexibility, instead of weakness which is often associated with adjectives relating to softness.

“The dissolution of the vessel that was once more recognisable as craft object simultaneously gives way to a misshapen form that begins to identify more as sculptural art through its ruptured deformity and textural ambivalence.”

(Quote from the exhibition essay)

One of the themes I explore in ‘Unbecoming’ is the perception of value, and how humankind has always tried to grasp ownership in the strangest of ways, such as through destruction. How does each person determine the value of things that have no ‘worth’, and what flicks the switch between ‘priceless’, and ‘worthless’? Does this object graduate from ‘craft object’ to ‘art’ simply because it has resulted from the process of destruction, making it unique like each one of us?

How will we be remembered if we cease to exist? In a world that is increasingly obsessed with ownership, the beauty of ephemerality slips by us in plain sight. Blink, and you miss it. A thinning soap bubble. A flicker of emotion. The lick of a flame before it claims something forever.

Does carving your name in stone make you live forever? Does immortality only exist when the physical form persists? Or does immortality come in the form of a memory, strengthened only by the absence of a physical form?

Installation View

Walking through the nylon yarn curtain, one is able to observe the vases displayed on glass and acrylic plinths that show off the intricacy of the lace with some shadow play. The vases are deliberately placed at a height lower than a usual gallery space, forcing the interaction between viewer and sculptures to be awkward. The audience is invited to stoop down to observe the works; in a way, bringing themselves down to the level of the vases. This once again brings to the fore, the unsaid question in the room: Is this craft, or art? Is art so, only because it is raised to be ‘worshipped’, and ‘untouchable’? In that same line of thought, is something that is ‘lower’ than us, like a crafted domestic object in a regular home, worthless just because we are able to come in contact with it?

Textile Hanging

Brother (2021)

This re-exhibited work was first commissioned for the exhibition, Of Limits in 2021. A work exploring the status of migrant workers in Singapore, highlighted especially when the COVID-19 pandemic hit our shores, this was the first piece of process-driven work that I created, which experimented with destruction.

Staged together with the video, the viewer experiences a different kind of ‘destruction’. While the fire in the Unbecoming series is uncontrollable and irreversible, one gets the sense of being ‘erased’ and ‘rewritten’ with the unravelling in this work. With the black paint on the surface of the fabric being the only evidence of the word having been painted on the knitted tapestry, this piece holds in it a sense of time, and history.

What You Could Be (2022)

A new artwork showing another form of destruction— deliberate and controlled.

Events

Organised with ArtScience Museum Singapore in conjunction with the Unbecoming exhibition was 2 Masterclass sessions, Making Nothing Out of Something at All. echoing themes of liberation through destruction. Participants were invited to ‘give themselves the permission’ to slow down through learning finger knitting, and then encouraged to undo their creation at the end of the session.

Have you ever taken the time out for yourself to be anti-productive? Calm fidgety fingers and the anxious mind through therapeutic motions, finally experiencing the catharsis of releasing your emotions when you undo your creation. Taking inspiration from Tenderhands by Ivetta Sunyoung Kang and Diary of 2020 by Eun Vivian Lee that are featured in Hope from Chaos: Pandemic Reflections exhibition, Kelly aims to extend the notion of healing and create a moment and space for reflection.

Craft in Conversation: Kelly Limerick & Adeline Kueh

What does it mean to have a craft-centred practice in today’s art scene? What are some challenges surrounding this, and how do artists navigate them? Join Kelly Limerick in conversation with artist-educator Adeline Kueh as they discuss these issues close to their heart and more.

Also on the second weekend was an artist talk with Adeline Kueh, where both artists spoke about their art practice relating to craft and labour.