October 6 - 26, 2023

La Wayaka Current (Desert) Residency Program in Calama, Chile

My obsession with the desert started far away from Chile, when I first started researching about the Gobi for an art biennial known as Land Art Mongolia (I was shortlisted but it got cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic). I have always been interested in residencies in foreign landscapes, and a year after I sent in my application, I was on my way to Santiago, Chile, my first time in either of the Americas.

Physical distance is a strange thing. When I touched down in Santiago after 30+ hours of flight and transits, my life in Singapore felt like years away. I developed a vague understanding of what people said of time and space being linked; somehow, my memories from literally 2 days ago were fuzzy, and felt unrelated to who I was at the moment.

View from plane window, en route to Calama

At the tiny Calama airport (2h flight from Santiago), a small group of strangers convened with bulky bags— the other airport dwellers (aside from the stray dogs we would soon be accustomed with) seemed to be from the mining industry. It was so lucky that almost all of us (in the group of 12) came from different countries; Japan, Belgium, Denmark, Italy, Canada, Australia, just to name a few. I immediately felt the excitement I always do when meeting people from different countries, for I know it promises a variety of perspectives.

The first long drive to the residency was a film, which ended at the boundaries of the pick-up’s window. My face froze with the wind, but the colours of the sky as we chased the sunset were like nothing I had ever seen before. Vast expanses of sand, dotted with ‘shrines’ for those who have died along the road, and scatterings of windmills.

Windmills in the distance

We finally tumbled into the house, located in a little town called Coyo; I remember the dogs welcoming us with barks, a little bit of talking, and then I was asleep. The next morning was our first breakfast experience at the large communal table. The bread and cold cheese, granola and yoghurt looked a bit dismal. But that was only the beginning of our great breakfast expeditions. Soon people were discovering the stovetop bread toaster (which could produce grilled cheese toasties and banana French toast), introducing avocado and homemade salt from the local plant Cachiyuyo. This plant survives by using the stronger roots of other plants for support, but also absorbs the salt from groundwater so other plants can survive. In other words, they have a symbiotic relationship, and thus the Cachiyuyo is seen to be very important by the locals. They are everywhere in the desert, and one of the staff members had ground up the salty leaves of those in the residency garden to use as table salt, adding to our delicious vegetarian meals.

On one of the first few mornings, we attended the Ayni ceremony, to give our offerings to the land. As Carlos, a local healer and our host performed the ceremony in the cold of desert mornings, I was struck by how similar the beliefs were to what I read about the Mongolians. Largely, it reminded me of the balance of Yin&Yang, as Carlos spoke about the balance of woman and man, death and life, dark and light. It also reminded me of concepts of dark, light, death and life in Ursula Le Guin’s The Tombs of Atuan (even more so as it is based in the desert).

I was particularly taken with the concept of Warmija (spelling differs as it is passed orally)— the perfect harmony that can be found between woman and man, resulting in one balanced being. There is also the belief of Pirgua- a single being that can be Warmija on its own. Carlos shared about how Pirgua are seen as blessings; he has a goat who has the head of a male goat, but the genitalia of a female goat. As male goats are aggressive, they often injure female goats while trying to mate. Carlos thus puts this gentle yet playful Pirgua goat into the enclosure with the females to get them ‘into the mood’, and only allows the male goats to ‘finish the act’. I knew at once that this was going to be the basis from which I created my artwork in the desert.

Carlos setting up the Mesa

Facing the grand Licancabur volcano, Carlos laid out a cloth representing a table, with vessels with ‘female’ and ‘male’ faces on them. Right represented life; Left represented death. We made offerings of coca leaves and red wine, respectively putting the offerings in the male vessels with our right hand, and the female with the left.

We were situated only 10 minutes walk from the desert, and most of the residents took morning or evening walks, going as far as the Moon Valley. I am glad for them because I was so engrossed in my work, I did not find the chance to walk around very much. One of the residents, the Danish sound artist Annegry was leaving after 10 days, and I was very glad to be a part of her work in which sand, stones, and other material were used to create a soundscape.

Us trekking across the desert to the Moon Valley (about 45 mins away; I got very burnt!)

Photo of me by Annegry, helping out with her sound installation in the desert

On Annegry’s last attempt, we followed Camilla to a secluded spot in the Moon Valley (about an hour’s trek from our home), where we sat in stillness to listen to the salt in the rocks crackle. The clayey soil there was so soft that if we had shouted, they might have crumbled. It was a wonder to see the magnificent formation of soil, marks of the water erosion from when this same place was under the ocean thousands of years before, stones and mica embedded everywhere. On my very last evening, I did one last trek to the Moon Valley with Elizabeth, where we chose a crevice and clambered up the clay to a private little cave, where we got marvellous views of the desert. It always calmed me to see the volcanos Licancabur and Laskar in the distance, and even more so in the evenings when they were dyed a musky pink. This was also why I chose Licancabur as the motif for one of the artworks I created during the residency, as I saw it as a ‘mother’ figure, overlooking us everywhere we went.

Sunrise silhouetting Licancabur on the morning of the Ayni Ceremony

At a certain point, I was starting to see desserts everywhere we went. It began during our visit to the salt mountain— the solidified salt formed a thin layer above the soil, which cracked as we stepped on it. Our footsteps sunk into the brown dirt beneath, as you would imagine a brownie with a chewy centre, generously sprinkled with icing sugar. The salt layer snapped like a well-baked tuile. The tiny stones presented themselves as chocolate rock candy. The soft soil that crumbled down the mountain was milk chocolate powder.

These photos were taken at the Tebenquiche salt flats, one of my favourite sites that we visited. The colours were just astounding.

Annegry shooting with her vintage camcorder

Another site I loved, an oasis with waterfalls in the middle of a desert valley

Holes in the ground used for ancient constellation-gazing

We had a night’s camp in the desert, where Carlos spoke about the constellations as seen by the locals, and I regret that I was so incredibly sleepy that I couldn’t catch the names. However, I did notice how different the positions of the stars visible from Singapore were. Living on the equator, the sky looks almost the same all the time; yet the sky in the Atacama looks different just ten minutes apart. Doze, and Orion has climbed up from below the horizon. Glance away, and Jupiter has risen. In the Jerez Valley, Carlos showed us large, round-bottom holes that had been carved out of the rock. They had been filled with water, and the pools had been used to read the constellations in the sky so they would know if the skies had shifted.

It was on the very last morning, at 5am while we were driving away from Coyo that I peered out the window looking for the moon. It didn’t seem to be there, until I looked out through the back window of the van— there was the moon; a peeled apple, sinking into the cushiony shadows of the mountain range as it bade us goodbye.

One of the petroglyphs we saw at Jerez Valley

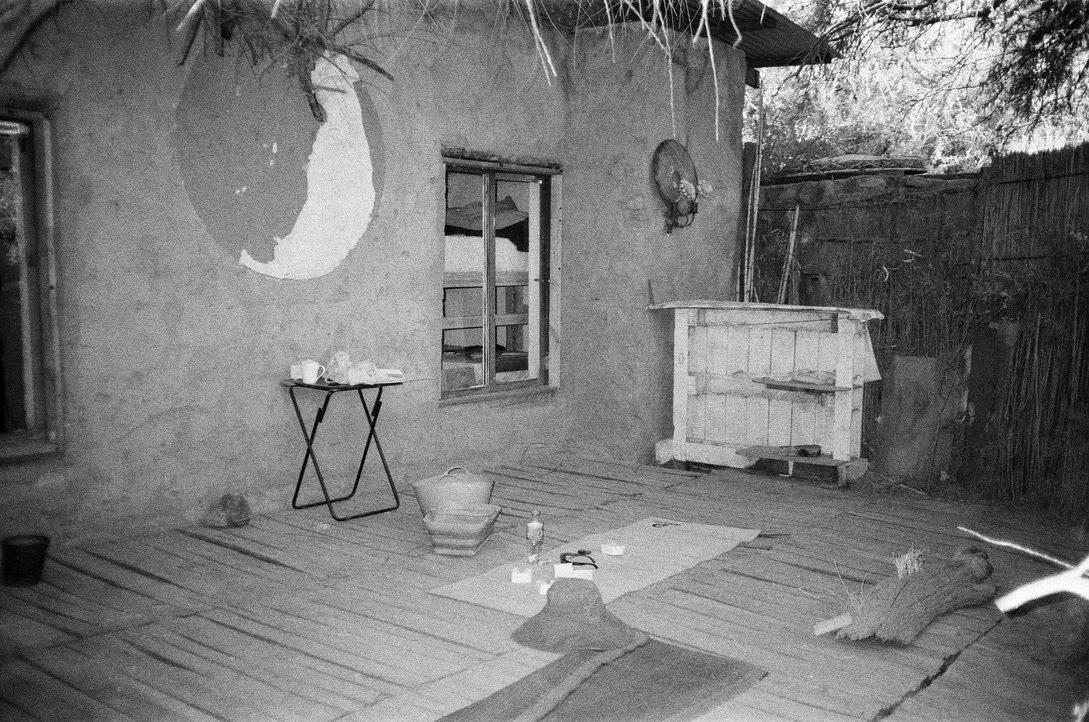

Photo of our ‘studio’ by Annegry

In between our trips to many different places, we carved out our own working spaces in Carlos’ and Sandra’s house, made by them using local materials like river stones over the years. Annegry started working in a little deck at the back of our shared room, and it became our little ‘studio’ space. It was terribly conducive and I started doing yoga there on a new handwoven rug I had bought. As I am rather still as I work, the cats and birds would often saunter or fly past, ignoring me completely. I’d stare up into the dry branches of the tree as I worked. And the best part of all was being completely disconnected from the internet for 3 weeks. We had a particular place in the garden known as ‘cyber’, where connection was strongest (but hopeless on weekends), and one particular chair at the dining table that seemed to command some connectivity. However, I found it was much easier to just work with the fact that there was no connection, and my time at the residency was incredibly productive.

Freshly shorn sheep wool at Gina’s place

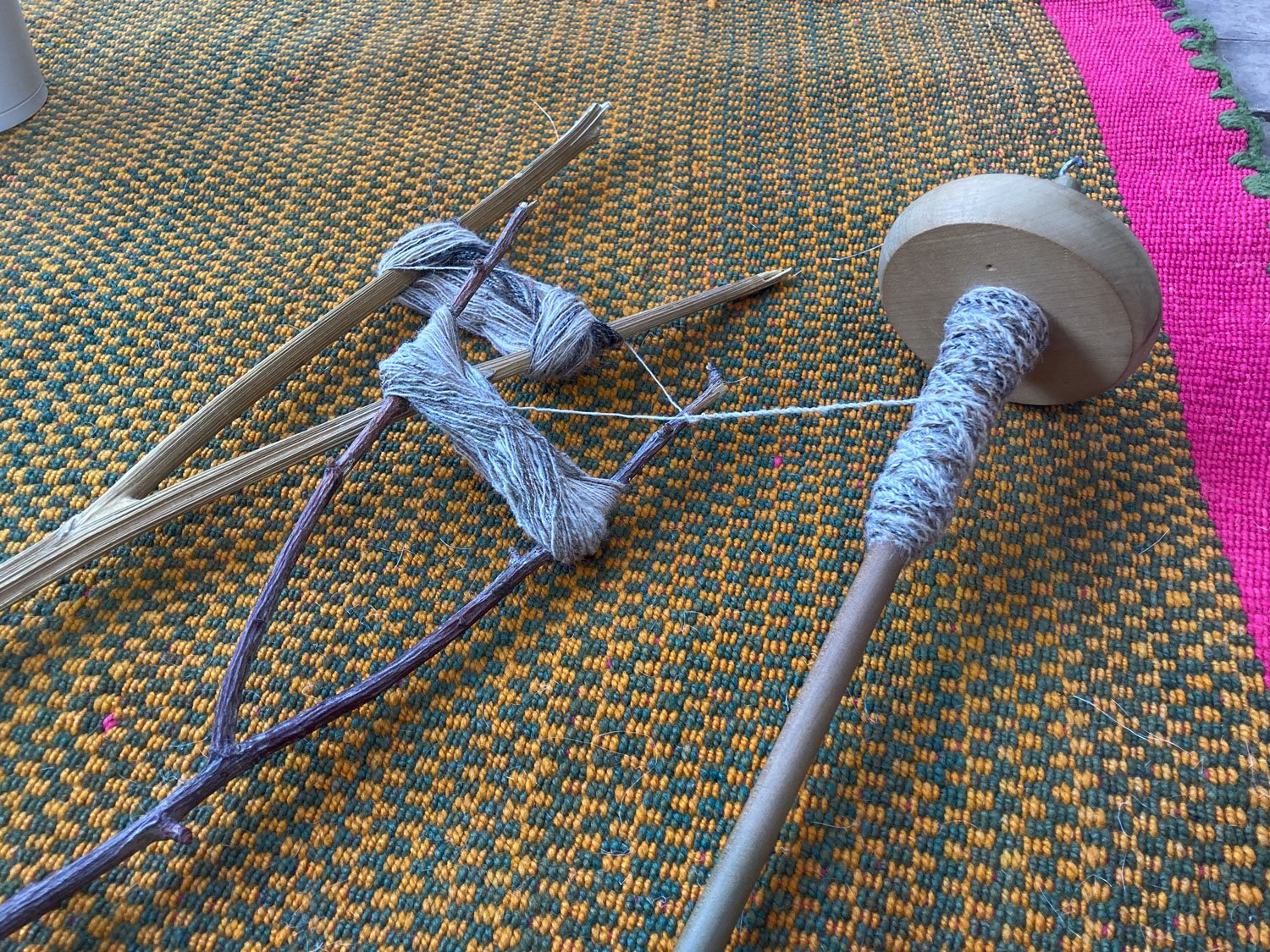

We were also very lucky to get a last minute workshop with Sandra’s aunt, Gina, who showed us the shorn wool from her sheeps, and how she spins yarn. I had already begun my own spinning then, and was struggling very hard at cleaning it. While I was desperately looking for a carding brush, which they didn’t sell in the region, Gina’s way was simply to pick out the unwanted matter by hand if she came across it. I learnt from Gina that she used the fibre as-is, and only washed it after the spinning and knitting was complete. The natural ‘wax’ on the fibre helps to hold the yarn together when spinning. It was also impressive that she was using a completely primitive supported spindle for her yarn; I am reliant on the hook of my drop spindle, and while I managed to create a length of yarn with the supported spindle, I reverted to my drop spindle for my actual work. She also sold us precious cactus spine needles, which I had been so keen to get my hands on. Her personal set, having been used for years, had developed a beautiful translucency.

Llama fur caught on branches of low trees as they graze

Huge cactuses at the altiplano, from which the cactus needles are gouged out from with a knife, then burnt at the tips

Process of creating II

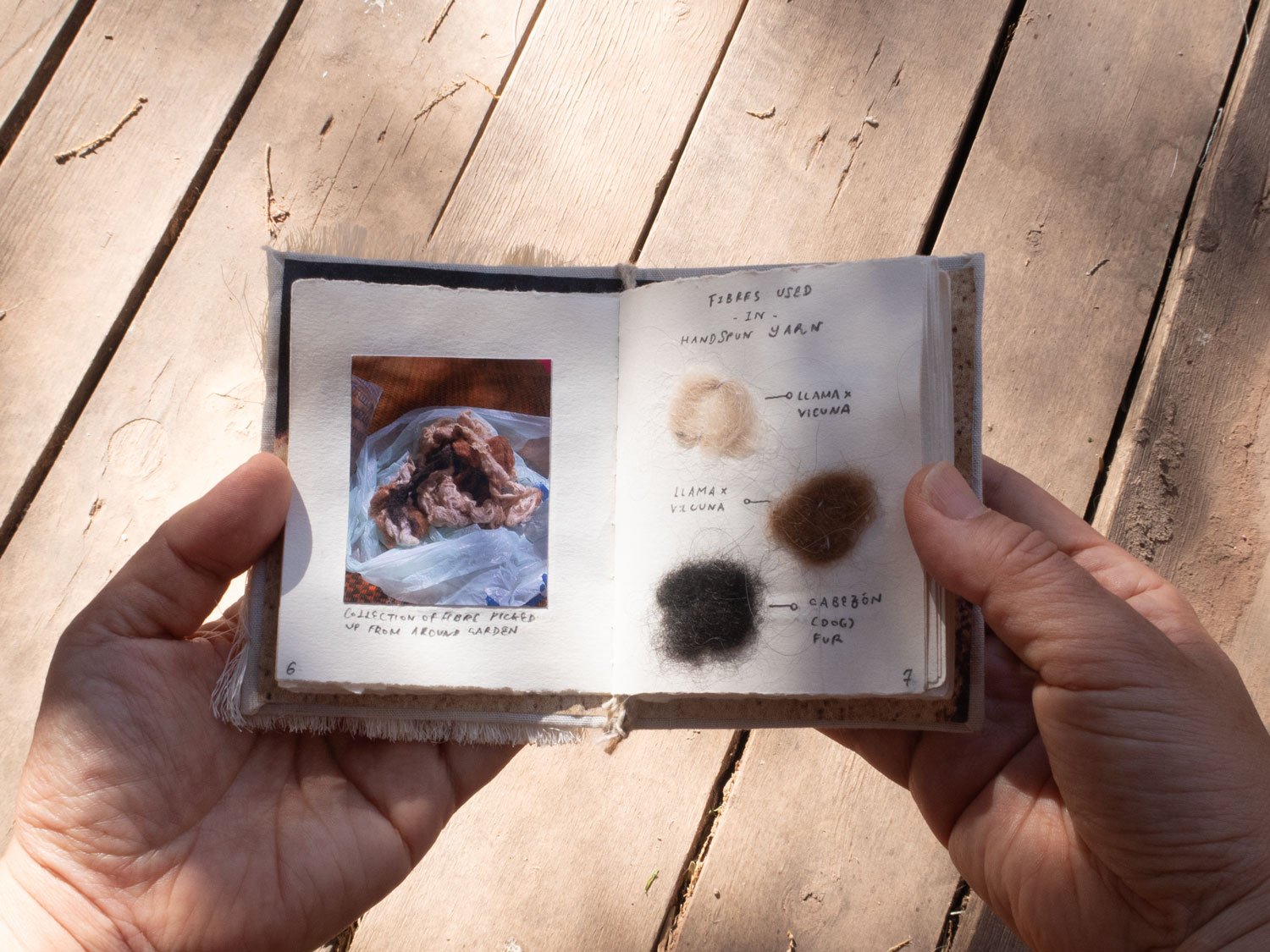

The above are some images of the fibre I foraged from around the garden (mostly the house dog and the tame vicuna-llama breed), and the 2 single-ply yarns I spun and wound onto Y-shaped branches, then plied into a 2-ply yarn ball. Single-ply yarn are often not balanced as they are twisted in one direction; plying 2 of the same direction in the opposite direction balances and stabilizes the yarn, another interpretation of the Warmija concept.

II, 2023. Yarn (llama-vicuna-dog fur) spun on hand spindle and locally-sourced alpaca yarn knitted on cactus needles

Image of II when viewed from the front

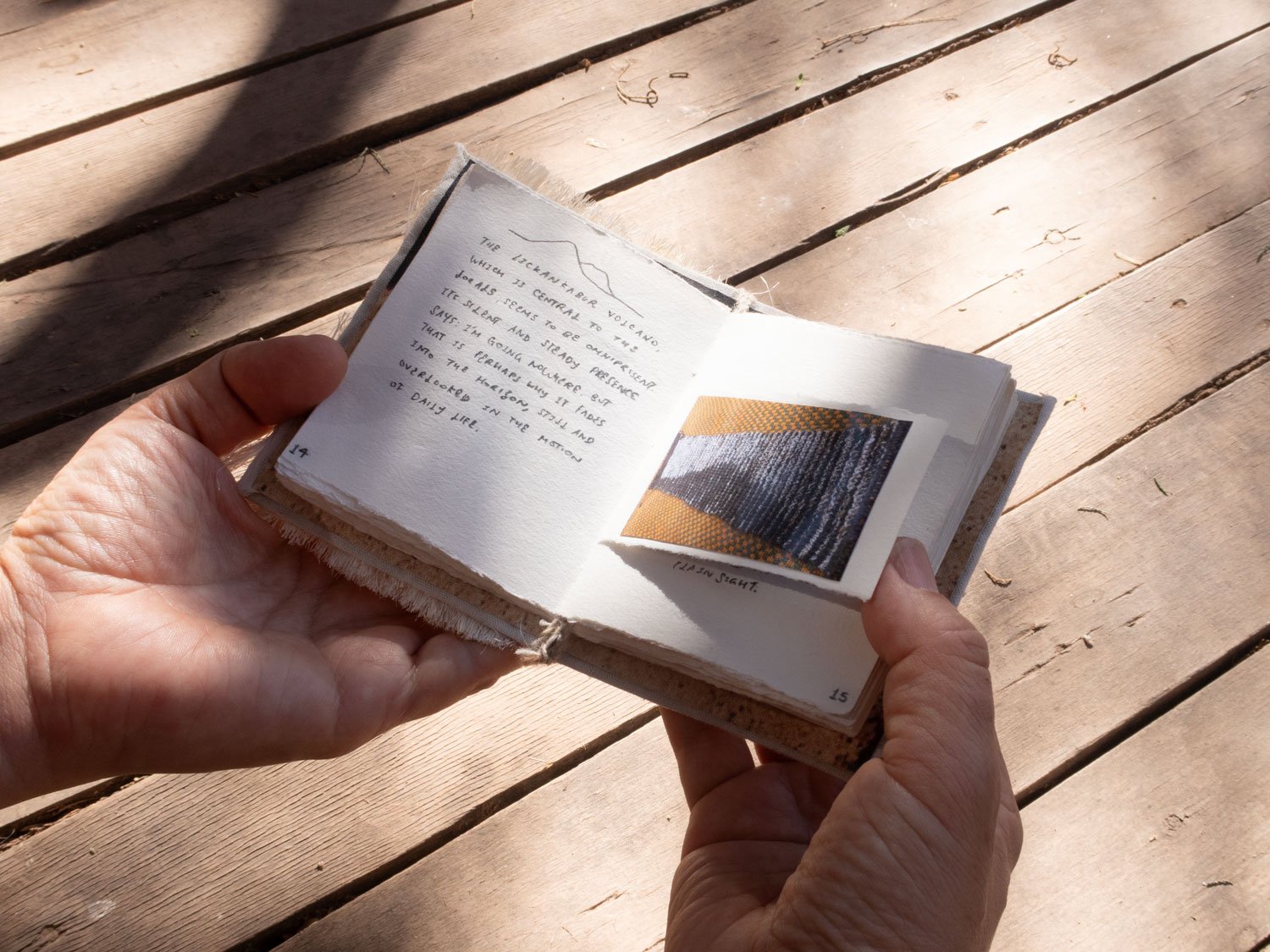

I decided to name this artwork II because it has more of an imagery of duality than the numeral 2. This knitted tapestry hints at the silhouette of Mount Licancabur, which reveals itself when viewed at an angle. Similar to how the shadows of mountain ridges change with the position of the sun, I used knitted ridges to create 'shadows' that form an illusion of the volcano.

As I mentioned, I saw Licancabur as a motherly figure; central to the local people, it seems to overlook the scene wherever we go. Its silent and steady presence tells us it is going nowhere, and perhaps that is why it fades into the horizon, still and forgotten in the motion of daily life, just as it hides itself in plain sight on the tapestry when viewed straight on.

The yarn I spun acted as the ‘light’ part of the tapestry; I sourced local alpaca yarn for the ‘dark’ parts. They were knitted and presented on cactus needles, which are of a fixed length and usually used in the round for circular knitting (socks, gloves).

Presentation of II, a sample of single-ply yarn, and a process zine during the exhibition in San Pedro town

Process of creating Mother’s Ritual

During our first introduction to the garden, I found myself spotting many long-fibre plants that could potentially be turned into spinning fibre. The one that caught my eye was the Malva plant, which has a beautiful flower and very long stem. I soaked the stems in water, then used a stone to crush the hard material within; incidentally, I discovered that the ‘foamy’ inner part of the Malva plant created a slimy consistency when in contact with water, which could be used as glue. I also learnt from the locals that they used this in the past to make marshmallow!

Process images of laying out the Malva fibre, drying with twigs and stones

Initially, I intended to collect enough Malva fibre to spin, but my skin was responding very badly to the dry climate and started cracking open. I could not continue soaking my hands in water and peeling off the fibre any longer as the water was going into all the cuts and cracks, and they refused to heal. Thankfully, I had brought along a bag of banana fibre from Singapore, and decided to use this with the Malva fibre to create an artwork ‘from the land, for the land’. In Singapore, due to the lack of space and permissions, it is difficult to create artworks in the environment and just leave them there, so I knew it was one thing I wanted to try while I was here. In the garden, I managed to forage a piece of cactus wood, which had long lines of holes in them resembling pores of the skin.

The above photos are my explorations preparing the rehydrated Malva fibre and banana fibre for ‘planting’ in the cactus wood. I also tried different styles of braiding; in the end, some of the braids were unbraided so the fibre took on a ‘permed’ appearance.

The huge cactuses at the Altiplano that also seemed to me like maternal figures, watching over us. The tiny cactus flowers would emerge from these ‘mothers’, and I saw it as a symbol of birth and fertility even in such tough conditions.

Process Zine

Malva flower

Due to the mode of presentation and language barrier (as most locals spoke only Spanish), I decided to create a process zine with photos so people could better understand my work. As I did not prepare the appropriate tools for binding, I had to make do with makeshift materials such as a repurposed paper bag for the cover, scrap cotton fabric from the garden, and pages torn from my personal sketchbook.

I wanted to include actual samples of the fibre pre-spun, and show the different appearances of the single and double ply yarn so people could understand the process even without words. I also wanted to find a way to include the painfully prickly yet beautiful fibres of the Malva flower. Pulling them out from the middle, I arranged them so one can see the beauty of its subtle gradient.

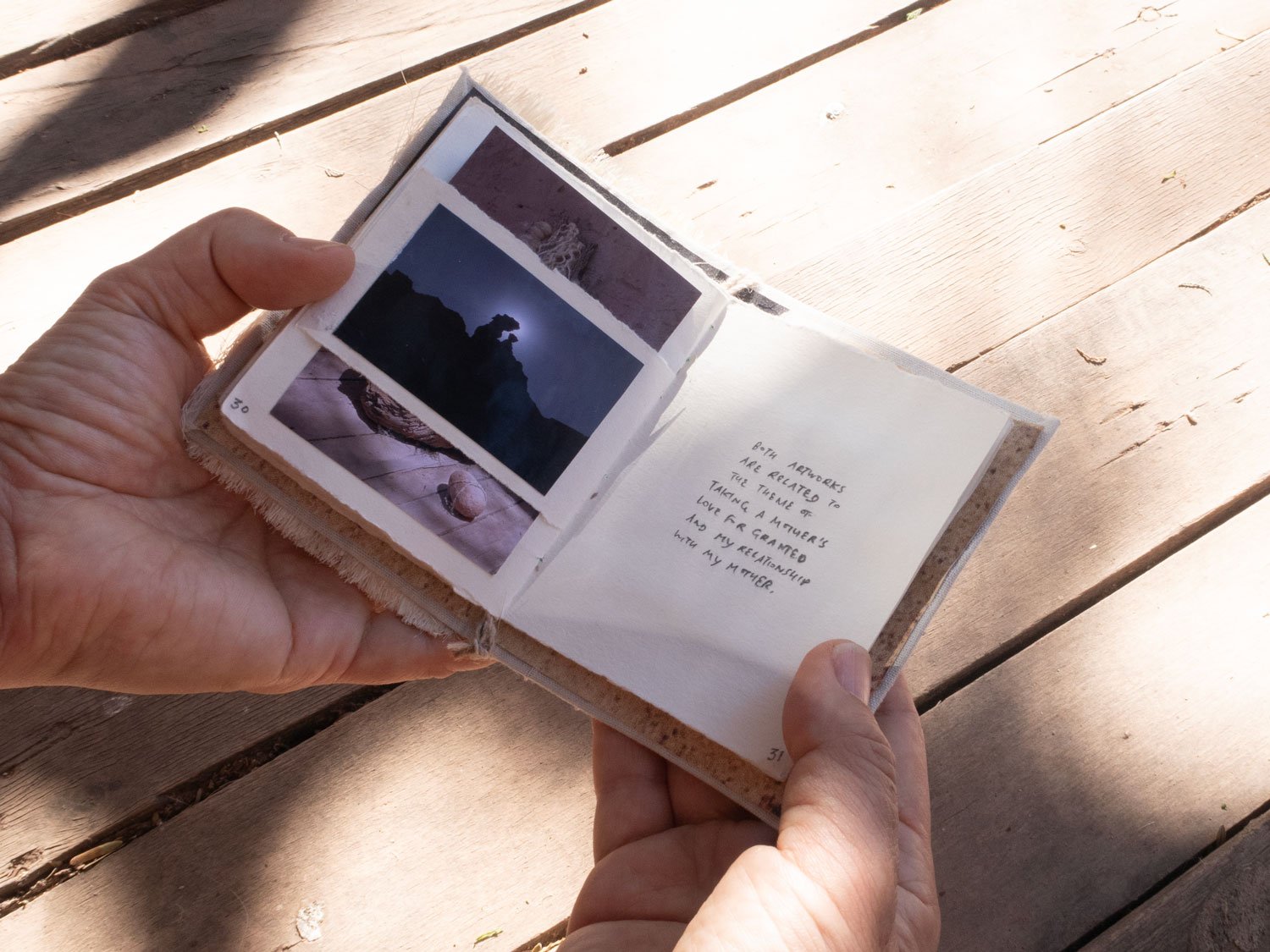

Both of the created artworks were inspired by and centred around the theme of motherhood; the natural act of protection, and how we often take this relationship for granted. This photo, which I shot at the salt mountain on our first field trip, seemed to be the perfect imagery for the mother-child relationship I have been exploring in my practice.

Me, Licancabur, Mother’s Ritual, and a little rock

When I got back to Singapore, I found that everything appeared to me in such high contrast. The greens of our trees became intense; the lines of the buildings vivid enough to hurt my eyes. I remember seeing my first view of the mountain range in Coyo upon arriving and thinking, oh I hope the sky is a little less foggy tomorrow so I get a clearer view! It wasn’t till a couple days later that I realised, this was the view. Was it the amount of sand in the air, throwing the light refractions off? The colours of the desert, and the softness of its lines, the flow of its sands, the curves of its shadows. How the light caressed each rock, each stone, teaching our eyes new things. These I will never forget. The silence, made with the whispers of the breeze. Feeling the first tickle of the sun, while freezing my toes off in the morning.

I will be back, surely.

This residency was made possible with the support from National Arts Council Singapore.