(All other Artwork photos courtesy of Joana Vasconcelos Website)

This first photo really does not do the work justice, but I decided it should be the header image— because I shot it. I remember walking past the entrance of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, deciding not to go in— and then this caught my eye. I kept trailing about in front of the entrance because it was closing time, and finally decided to make changes to my plans and come back here a couple of days later.

I did not regret it.

Visiting the Summer Exhibition changed my life. Grayson Perry was curating that year, and the walls were a cheerful yellow. The art wasn’t boring. They made me gasp, and laugh, and time flew by. And this! I just kept coming back to it.

As a crochet artist, I am quite picky about the kind of textile art I like. Sometimes, knowing the technicalities makes things a little less impressive. But some work just takes my breath away, because I think, “I would NEVER have thought of that,” or “I have NO IDEA how they did that”.

Joana Vasconcelos’ work is one of those. It isn’t just the sheer magnificence of her large installations such as the one I encountered, but her entire portfolio that has me nodding away and putting my nose up to my screen surveying details. I love consistent artists; a stable line of thought and honesty to the self that runs through all their work, whether big or small, 2D or 3D. And Vasconcelos is not just a textile artist, but uses textile as one of the many mediums in which she expresses herself.

It is clear that contemporary artists require more than just a stoicism towards their craft to bring their work to another level, and Vasconcelos proves that with her 25 years of practice. While she is recognised for her popular work like the Valkyries series or doily-wrapped animal statues— no doubt showing a deep understanding of the medium— it is her other assemblages and kinetic installations that gives me a dose of the artist’s wit, which she uses to ‘[create] a bridge between the domestic environment and public space’.

To be an artist like Vasconcelos, who was the youngest and first ever female artist in the Palace of Versailles in 2012, I imagine dedication, discipline and an organised mind— things so underrated, but so important in artists.

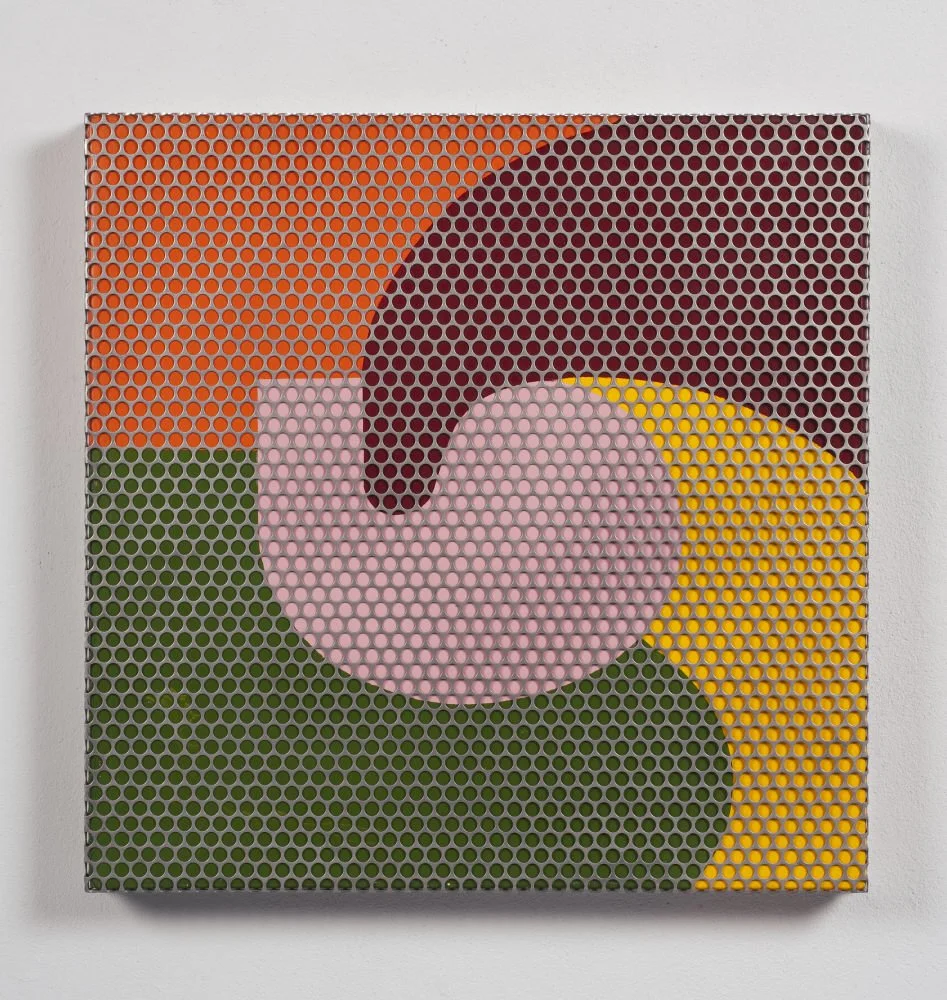

Shapes & Balance

I was quite surprised when I dug into Vasconcelos’ portfolio and found her paintings, but I immediately understood how her understanding of colours and balance came to be. In them you can already see her inclination towards certain shapes that seems to have inspired the form of her Valkyries. She also started using found objects like plastic packaging in her paintings from as early as 1997, which was later expanded on in her installation series Hearts. Comparing the two paintings above, which are created over 10 years apart, one can observe a consistent tone, yet an obvious growth in the complexity of the composition in the more recent piece. They share a similar message (and title) about over-consumption, a theme Vasconcelos holds close to her throughout her practice.

Close-up of plastic cutlery making up Golden Independent Heart, 2004.

Grelha [Grid], 2003

I’ve always held to the belief that exploring different mediums allows you to perceive all mediums with less boundaries, invoking new methods of creation that go on to inform the next work. With Hiperconsumo (2010), her flat colour, hard-edged painting style remains, yet there is a detectable sensitivity to layers; the painting acquires a certain depth, which hints at the compositions of 3D work she has been exploring. Additionally, the transparent packaging is no longer isolated; it reaches the edges of the canvas, forming a deliberate whisper of a texture atop the painting, cleverly suggesting stacked shapes. In other paintings, ‘porous’ materials with repetitive patterns such as metal grids act as a pattern filling the coloured forms. It is perhaps this process of manually layering materials that inspires patterns within a bound shape, such as patterns on a textile, as well as composition of sculptures within a space.

Gateway, 2019. Tiled swimming pool by Joana Vasconcelos, created with 11,366 tiles painted and glazed by hand in a century-old factory in Portugal. The outline of the pool, with its ‘droplet’ edges, is iconically Vasconcelos.

Composition & Space

One of the struggles I feel many textile artists share, is projecting our work into a ‘space’. As most textile crafts begin small (in fact, the finer, the ‘better’), it takes conscious practice to design our work to extend into a space, especially one that is not a fixed cube, or even consider it as part of the architecture like Gateway (2019), a functional swimming pool. Many textile crafts also decorate the ‘surface’ more than suggest form; embroidery, lace-making and macramé, are a few that are popularly created ‘flat’. From where then, does the form spring?

Valquíria #1 [Valkyrie #1], 2004

In 2004, Vasconcelos created her first free-hanging soft sculpture— aptly-named after the Norse mythological figure Valkyrie, often depicted to be flying. The first interpretation of her paintings into a 3D object extending into space had been born. Using crochet and textiles in her work was not new, however; she first introduced soft crochet forms in 2001 with her wall-hanging sculpture, Pantelmina #1 (2001), and Pega #1 [Potholder #1] (2002), and the colour and materiality of this first Valkyrie seemed largely-inspired by those. However, the evolution of its form into a ‘floating’ sculpture gave a new facet to her work, which would later propel her artwork into various unconventional spaces and turn into one of her ‘trademarks’.

Pantelmina #1, 2001. One of Vasconcelos’ first few soft sculptures that was created with crochet. She accentuates the soft quality of the crochet form by binding it with belts, forming bulges that seem to want to escape. She often explores the status of women with her works, and this suggests to me a restriction of soft, feminine power, which finds its strength through malleability.

Pega #1 [Potholder #1], 2002. Similar to ‘Pantelmina’, this soft sculpture (part of a series she terms ‘Pot Holders’) is tacked to a wall, bringing emphasis to the flexibility of crochet and the tension that comes with it.

Raffinée, 2003. An early exploration of scale before the Valkyries series, a blown-up version of Pantelmina #1.

While her wall-hanging soft sculptures seemed to suggest the notion of being ‘trapped’, her Valkyries were the exact opposite; they flew freely, invading spaces unapologetically, forcing one to walk about them. As the series grew, we see the materiality evolve as well. Early on, they seem to emulate her paintings, and borrow from the traditional, folk-crafted pot holder from the kitchen. The Valkyries soon introduced a variety of textures like fringe, tassels, and even lights in the later years, all of which added to the illusion of movement, flight, and a majestic presence.

Mary Poppins, 2010. Installed in the Palace of Versailles in 2012. This exhibition welcomed 1.6 million visitors, a record high in France in 50 years.

Golden Valkyrie, 2012. With a sensitivity to the space inhabited, this Valkyrie introduced metallic elements that brought a sheen; we start to see Vasconcelos’ exploration with new material and the confidence with which she incorporated them, into a form she was growing to be a master of.

Amazônia, 2014. The use of fringe adds almost ‘translucent’ layers and wavering shadows as they move with air currents.

Amazônia, 2014. Ruffled organza trim a part of this Valkyrie that decides not to pay heed to the staircase.

Needless to say, SCALE was of huge importance to her Valkyries series, but not just the overall size. Her prior experience in composition in her paintings probably helped with the balance of shapes and colours. Comparing her first Valkyrie to her later ones, we can see more variety in the size of the patterns as they grew. The earlier crochet works seemed to take the unit size of crochet stitches as they were, making the concentrations of colour quite regular and ‘predictable’. In the later works, the patterns took on random shapes and sizes, breaking away from horizontal and vertical lines, which gave the Valkyries a dynamic quality that appeals to your eye time and again. Most importantly, she had found in the form of the Valkyries what was missing from the ‘Pantelmina’ work even when enlarged— an iconic look that persevered even when rearranged to fit into almost any conceivable space, or changed in colour or materiality; that bulbous, ‘droplet’-shaped form that now extended through vertical stairwells and long, grand halls.

Valquíria Enxoval [Valkyrie Trousseau], 2009. 14m long sculpture exhibited in the Palace of Versailles in 2013. Made in collaboration with the artisans of Nisa, a small countryside village in Portugal known for its rich history of crafts.

It's Raining Men, 2018. Made up men’s shirts and ties, this Valkyrie monstered its way through doorways and corridors of the building.

It's Raining Men, 2018. Lapels, belts, and other elements of menswear is used, yet the Valkyrie form is still distinct.

Materiality & Movement

Blup, 2002. First of her ‘Boxes’ series, an ongoing series which explores crochet forms bulging out from wall-fixed boxes, usually tiled.

Pretty in Pink, 2015. One of her latest pieces from the ‘Boxes’ series, which includes new materials similar to that of her Valkyries. In a way, this seems like a ‘collectable’ Valkyrie, borne of her material explorations in that separate series.

Prior to the introduction of textile materials into her work in 2001, Vasconcelos worked largely with found material, with the closest material to textile being hair— another strong symbol of femininity. Her earlier iterations of crochet sculptures also involved ‘hard’ elements, one of which being tiles, a recurrent material in her work. The exposure to these different objects in her earlier work added to her experience of manipulating different materials and thinking beyond the realms of textile.

Mise, 2000. Vasconcelos often used found objects related to domesticity or femininity.

Una Dirección, 2003. A simple intervention using hair on the Q-poles.

While textile became more predominant in her practice later on, the idea of domesticity and linkage to items associated with the home and womanhood has been an undercurrent from the start. It is perhaps only natural that textile and a home-made craft such as crochet was introduced later on, as she continually questions the fine line between art and domestic labour. While some artists become specialised in the medium they are best known for, it could be the very same thing that binds them in that medium, rendering them unable to ideate outside that capacity. By being led by the artist voice and several strong themes, the work naturally forms a cohesive body of works regardless of medium.

A Todo o Vapor (Verde) [Full Steam Ahead (Green)] #1/3, 2013.

Flores do Meu Desejo [Flowers of My Desire], 1996-2010. One of Vasconcelos earlier works, using the domestic feather duster to form a ‘flower’ wall.

Dorothy, 2007-2010. First conceived in 2007, the ‘Cinderella’ open-toe heel assembled from domestic pots has become one of Vasconcelos’ iconic pieces. It has taken on many iterations under different female names, and displayed in various exhibitions.

One of Vasconcelos’ most known works would be her ‘Shoes’ series, featuring a huge open-toe stiletto made up of the humble, shiny pot you might find in your kitchen. The first of the series named ‘Cinderella’, seems a perfect name for a girl relegated to housework, who then turns into a princess in a shiny dress. The sparkling, humble pots turn into a symbol of elegant womanhood; such juxtaposition is one often played by the artist, who decontextualises items we can easily find in our daily lives to question the contradictions of society.

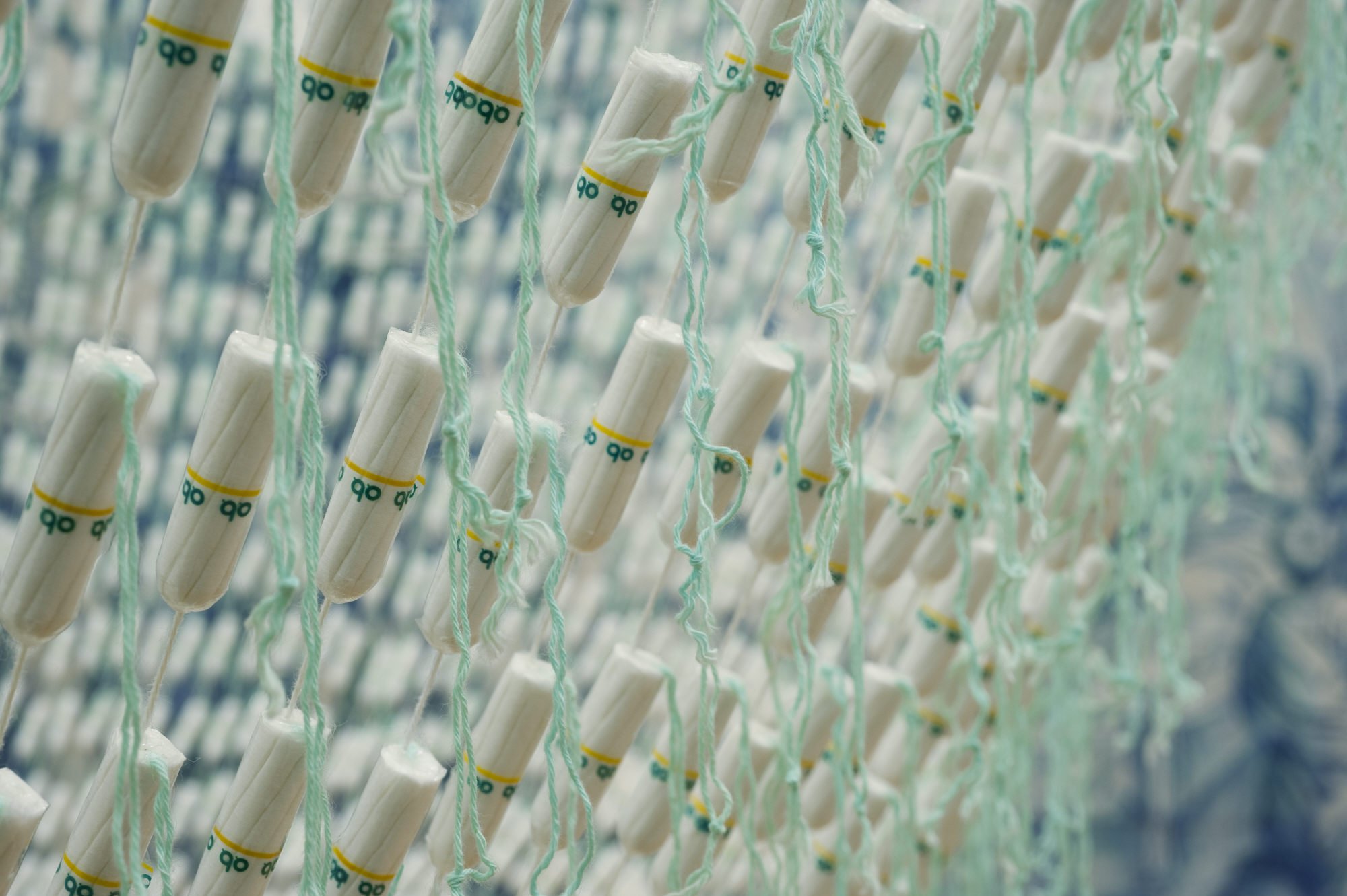

A Noiva [The Bride], 2001-2005.

A Noiva [The Bride], 2001-2005. Close-up showing tampons.

However, my favourite of all her work of assembled readymades must undoubtedly be the cleverly-named A Noiva [The Bride] (2001-2005), which was presented at the Venice Biennale in 2005. Made up of 25,000 tampons, the massive, 6m-tall chandelier must have been a sight to behold at such a grand-scale event, and shocking (in a good way) with its boldness. If it had been a one-off, it might have been a stunt; but her ongoing explorations of the relationship between womanhood and society lend to each other and strengthens her entire body of work.

Some of her assemblages do not directly comment on the usual themes of womanhood; yet they suggest a threatening of this ‘soft energy’ with the overwhelming presence of ‘masculine’ icons often suggesting violence. In War Games (2011), a car wears rifles as its jacket; an array of soft toys sit smiling innocently in it while the rifles on the bonnet point straight into the car, suggesting the innocence that gets in the line of fire more often that not during wars.

War Games, 2011.

Call Center, 2014-2016.

The beauty of readymades is the personality they already have and the connotations that come with it, giving you great tools for making a story. On the contrary, work created from craft (such as many textile mediums) are free to be manipulated in any way, and mostly begin with a blank canvas. Vasconcelos seems to hold an apparent mastery over both, producing works that question society with a clever use of material, and others that simply wow with scale and attention to craftsmanship and sensitivity to colours and form.

Wash and Go, 1998. Silk stockings of all colours hang from two ‘spinners’ that mimic a car wash when you walk through them.

Perhaps, some of my favourite works of Vasconcelos’ are not because they are a form of textile; I am particularly taken by her works that introduce movement. From as early as 1998, she has explored moving parts in her work that accentuate the story she is trying to tell. In Wash and Go (1998), the installation comes to life immediately with movement, making the artwork self-explanatory. It is also this aspect of the artist’s work that I admire— the ability to capture audiences without a lengthy explanation, encapsulating the idea with a very simple title that says it all. It also takes knowledge of material (the type of textile) to predict how it would react when spun; and the effect was truly reminiscent of an actual carwash.

Burka, 2002

This knowledge of and sensitivity to textiles comes through even more in Burka (2002). The set-up is fairly simple— the soft sculpture is lifted slowly in the air, held at the highest point and then suddenly released, making a loud sound as it hits the ground. It is evident Vasconcelos is a great storyteller— the drama and suspense, followed by the climax, and then relief when we remind ourselves this is just fabric, all in under a minute. It takes an understanding of the fabric and how it is put together, to achieve the intended effect so well; first as a clothed human figure (as the name of the work might suggest) as if seated or kneeling, then to one standing up, and finally, at the highest point, a shadow of the gallows. And, in the horror of the falling ‘figure’ in that split second, one cannot help but admire how the fabric billows and reveals all the layers; a thing of beauty, even in death.

Fashion Victims #2, 2018. While there are no videos, pictures suggest this is a kinetic sculpture, as the ‘victims’ were originally completely unbound.

In Fashion Victims #2 (2018), the set-up is clearly inspired by an industrial knitting machine, with the spools of different coloured yarn and feeders; except the naked ‘victims’ are being bound and ‘blindfolded’, instead of having clothes made for them. Consumerism being one of the themes Vasconcelos explores with her work, this suggests how we are becoming victims of the fast fashion world, ‘blinded’ by marketing strategies and bound by trends, to the point we are unable to have the freedom to think for ourselves.

While this art piece does not use textile as its main medium (considering the threads are used without manipulation), its form suggests a knowledge of the technicality behind textile production, starting a conversation about textile and its fate in the current world, without actually engaging in a textile practice.

Recontextualising

Matilha [Pack of Dogs], 2005

Prior to encountering the Royal Valkyrie in the Royal Academy that fateful Summer’s day, I had unknowingly come across Vasconcelos’ work online; but as the Internet these days go, there was either no credit or I did not remember it. Seeing these images of ceramic sculptures covered in crocheted doilies brought back the memory immediately.

I’d think most people who crochet enjoy making doilies. They are pretty, technically challenging, therapeutic… but there’s only so much you can do with doilies. This is one of the reasons doilies are a popular choice to go with in yarnbombing, along with the fact that they come in loose pieces and can easily be manipulated through sewing to ‘wrap’ an unevenly-shaped object.

Gorette, 2006

I don’t think I can say with as much confidence though, that everyone can wrap a considerably small object (with many protrusions at that) with such precision and artistry. In Gorette (2006), the symmetry and choice of doilies in different sizes and styles is obviously a result of long deliberation and planning. It is with these pieces that the artist’s eye for quality and respect for craftsmanship comes through.

Enamorados [In Love], 2005. The urinal series by Vasconcelos is a symbol of feminism and also gay love.

It is not just traditional, white doilies she explores though; Vasconcelos has a series of Urinals wrapped in crochet of all colours and styles, an ode to Marcel Duchamp, who she considers ‘the master of contemporary thought in sculpture’, and a huge influence in the usage of readymades in her work.

Putting two urinals together and joining them up with crochet, Vasconcelos sees these works as a symbol of feminism and also gay love. While covering readymades in crochet is not a new practice, her choice of object gives the work her voice. Lace, with its intricacy, connotations of domestic labour and sympathetic quality, easily overrides the original personality of an object, and the artist cleverly makes use of this trait to recontextualise these common objects and imbue them with a new personality.

Minerva, 2005

While Vasconcelos’ portfolio extends far beyond my writing, I wanted to follow her journey from the start to understand the origins of her work, and try to observe it from the perspective of a textile practitioner. I started writing this article in May 2021, and am only finishing it in October 2022, because her portfolio was so extensive that I was exhausted just going through everything!

It was truly enlightening to research Joana Vasconcelos, and it affirms my beliefs that an artist with a consistent voice can only be so through lots of experience, dedication and an openness to all mediums. It’s difficult to become a master of your medium, or have a strong artist voice and concepts, but much more difficult to be able in both.

“Materials and techniques serve the needs of artists as a result of intention and choice, not by happenstance or accident. The making of art is dependent on a series of choices as to how and when to utilise a specific material, and how best to transform material— to give it form— through specific behaviours and actions.”

![Consumo [Consumption], 1997](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56ae02ce8a65e2c82881ee57/1620713042280-NBKDTXDGQUL5HLOG1ZWP/Consumo+%5BConsumption%5D%2C+1997.jpg)

![Hiperconsumo [Hyperconsumption], 2010.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56ae02ce8a65e2c82881ee57/1620713300338-FW44DHUZHVHVNAF1WRRW/Hiperconsumo+%5BHyperconsumption%5D%2C+2010.jpg)